The Second “S” in CSS

💡

Essential Question: Essential Question: How does a web browser know that the “sheet” exists and know to use it when applying styles on a page?

CSS is an abbreviation for Cascading Style Sheets. We’ve established that in the lessons so far.

While most of the discussion about CSS on the web (or even here on CSS-Tricks) is centered around writing styles and how the cascade affects them, what we don’t talk a whole lot about is the sheet part of the language. So let’s give that lonely second “S” a little bit of the spotlight and understand what we mean when we say CSS is a style sheet.

The Sheet Contains the Styles

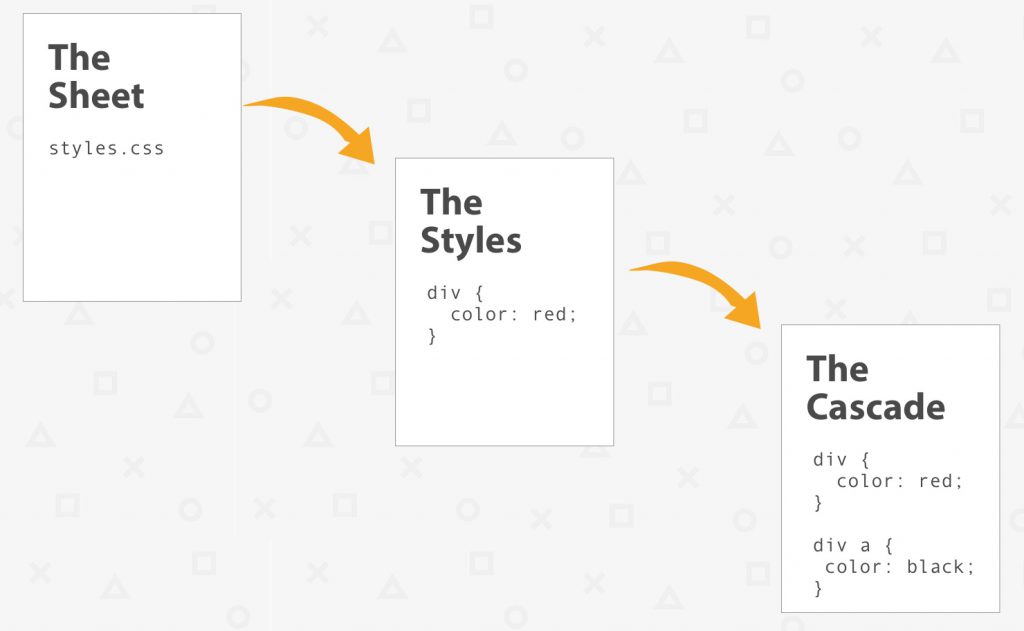

The cascade describes how styles interact with one another. The styles make up the actual code. Then there’s the sheet that contains that code. Like a sheet of paper that we write on, the “sheet” of CSS is the digital file where styles are coded.

If we were to illustrate this, the relationship between the three sort of forms a cascade:

There can be multiple sheets all continuing multiple styles all associated with one HTML document. The combination of those and the processes of figuring out what styles take precedence to style what elements is called the cascade (That first “C” in CSS).

The Sheet is a Digital File

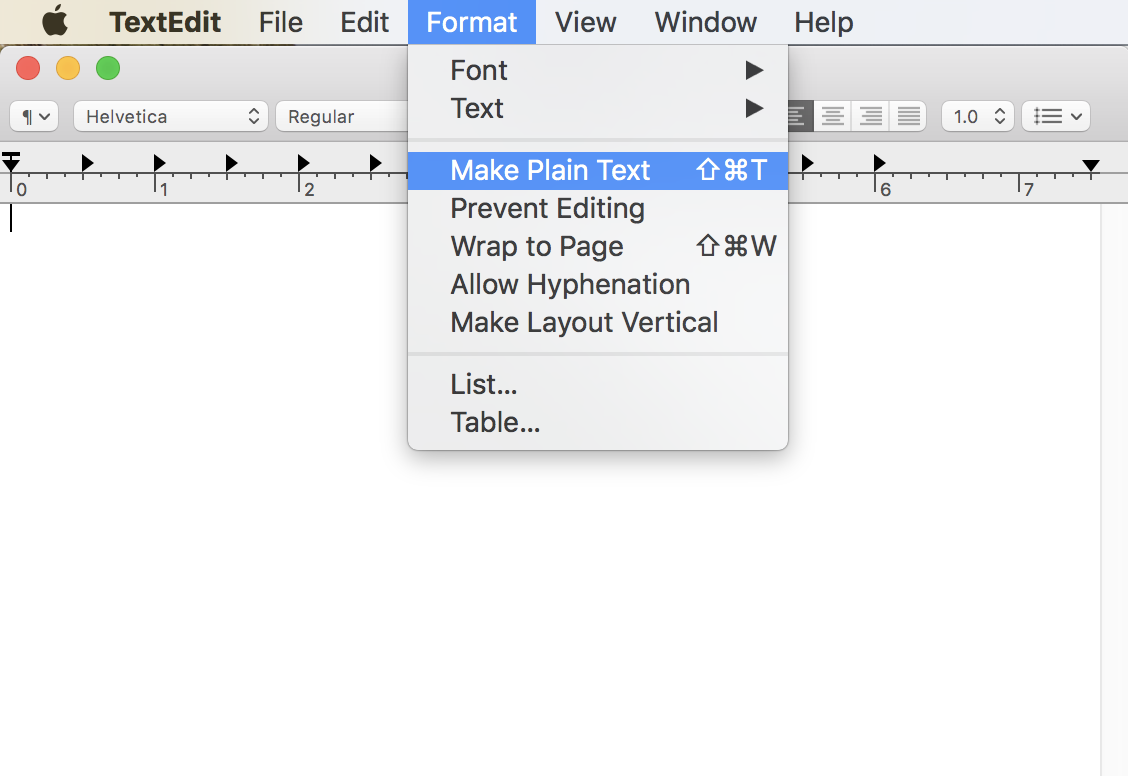

The sheet is such a special thing that it’s been given its own file extension: .css. You have the power to create these files on your own. Creating a CSS file can be done in any text editor. They are literally text files. Not “rich text” documents or Word documents, but plain ol’ text.

If you’re on Mac, then you can fire up TextEdit to start writing CSS. Just make sure it’s in “Plain Text” mode.

If you’re on Windows, the default Notepad app is the equivalent. Heck, you can type styles in just about any plain text editor to write CSS, even if that’s not what it says it was designed to do.

Whatever tool you use, the key is to save your document as a .css file. This can usually be done by simply add that to your file name when saving. Here’s how that looks in TextEdit:

⚠️ Auto-Playing Media

Seriously, the choice of which text editor to use for writing CSS is totally up to you. There are many, many to choose from, but here are a few popular ones:

You might reach for one of those because they’ll do handy things for you, like syntax highlight the code (colorize different parts to help it be easier to understand what is what).

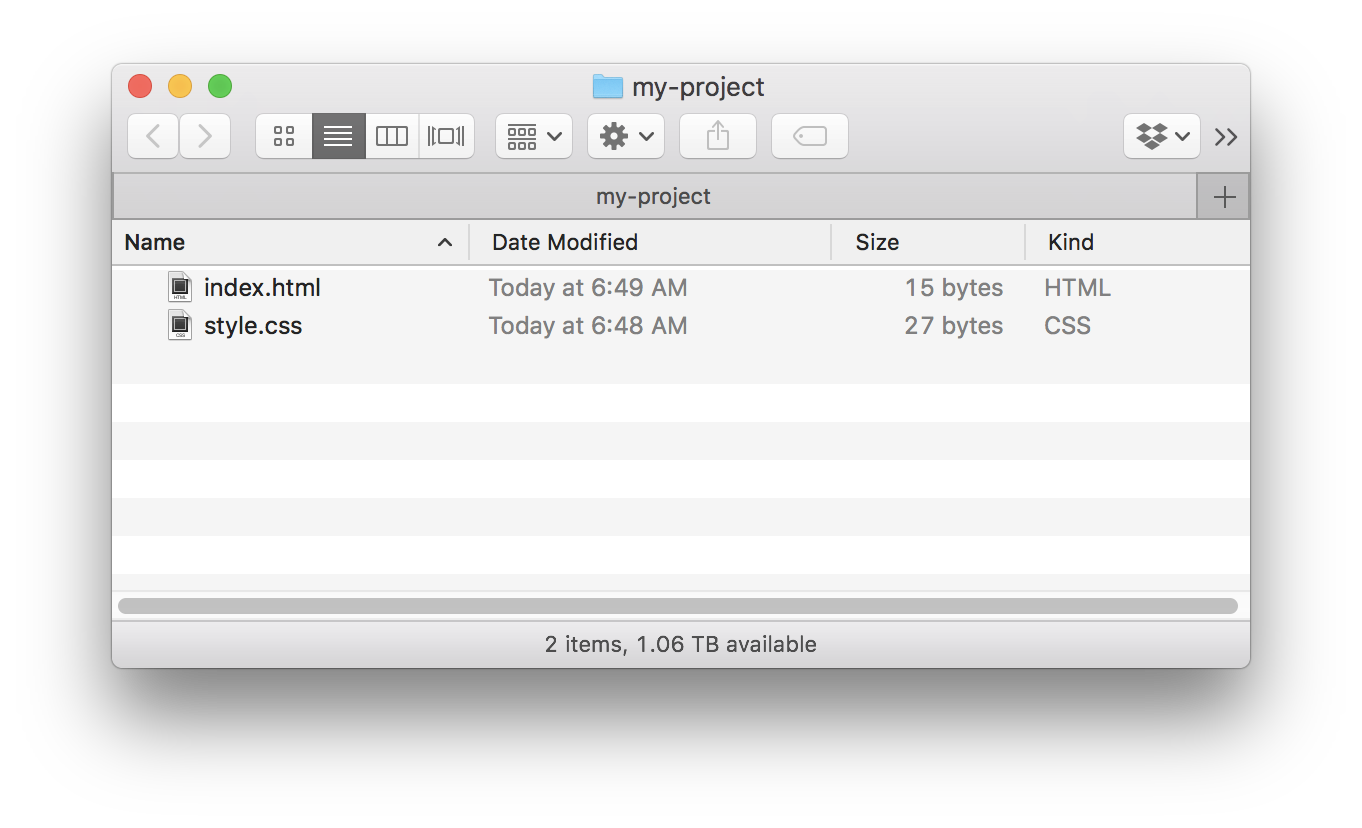

Hey look I made some files completely from scratch with my text editor:

Those files are 100% valid in any web browser, new or old. We’ve quite literally just made a website.

The Sheet is Linked Up to the HTML

We do need to connect the HTML and CSS, though. Make sure the styles we wrote in our sheet get loaded onto the web page.

A webpage without CSS is pretty barebones. See for yourself.

Once we link up the CSS file, voila!

How did that happen? if you look at the top of any webpage, there’s going to be a tag that contains information about the HTML document:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<!-- a bunch of other stuff -->

</head>

<body>

<!-- the page content -->

</body>

</html>Even though the code inside might look odd, there is typically one line (or more if we’re using multiple stylesheets) that references the sheet. It looks something like this:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<!-- a bunch of other stuff -->

</head>

<body>

<!-- the page content -->

</body>

</html>This line tells the web browser as it reads this HTML file:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<!-- a bunch of other stuff -->

</head>

<body>

<!-- the page content -->

</body>

</html>Even though the code inside the <head> might look odd; there is typically one line (or more if we’re using multiple stylesheets) that references the sheet. It looks something like this:

<head>

<link rel="stylesheet" type="text/css" href="styles.css" />

</head>This line tells the web browser as it reads the HTML file::

- I’d like to link up a style sheet

- Here’s where it is located

You can name the sheet whatever you want:

styles.cssglobal.cssseriously-whatever-you-want.css

The important thing is to give the correct location of the CSS file, whether that’s on your web server, a CDN or some other server altogether.

Here are a few examples:

<head>

<!-- CSS on my server in the top level directory -->

<link rel="stylesheet" type="text/css" href="styles.css">

<!-- CSS on my server in another directory -->

<link rel="stylesheet" type="text/css" href="/css/styles.css">

<!-- CSS on another server -->

<link rel="stylesheet" type="text/css" href="https://some-other-site/path/to/styles.css"> </head> The Sheet is Not Required for HTML

You saw the example of a barebones web page above. No web page is required to use a stylesheet.

Also, we can technically write CSS directly in the HTML using the HTML style attribute. This is called inline styling, and it goes a little something like this if you imagine you’re looking at the code of an HTML file:<h1>A Headline</h1> <p>Some paragraph content.</p> <!– and so on –>

While that’s possible, there are three serious strikes against writing styles this way:

- If you decide to use a stylesheet later, it is extremely difficult to override inline styles with the styles in the HTML. Inline styles take priority over styles in a sheet.

- Maintaining all of those styles is tough if you need to make a “quick” change, and it makes the HTML hard to read.

- There’s something weird about saying we’re writing CSS inline when there really is no cascade or sheet. All we’re really writing are styles.

There is a second way to write CSS in HTML and that’s directly in the <head> or in a <style> tag:

<head>

<style>

h1 {

color: #333;

font-size: 24px;

line-height: 36px;

}

p {

color: #000;

font-size: 16px;

line-height: 24px;

}

</style>

</head>That does indeed make the HTML easier to read, already making it better than inline styling. Still, it’s hard to manage all styles this way because it has to be managed on each and every webpage of a site, meaning one “quick” change might have to be done several times, depending on how many pages we’re dealing with.

An external sheet that can be called once in the <head> is usually your best bet.

The Sheet is Important

I hope that you’re starting to see the importance of the sheet by this point. It’s a core part of writing CSS. Without it, styles would be difficult to manage, HTML would get cluttered, and the cascade would be nonexistent in at least one case.

The sheet is the core component of CSS. Sure, it often appears to play second fiddle to the first “S,” but perhaps that’s because we all have a quiet understanding of its importance.

Watch Me Do It

The only way to get a stylesheet working is to link it up to an HTML document so that the web browser knows it exists and needs to look at it when rendering HTML on a page. Watch the following video for a demonstration of how to link a stylesheet to an HTML document.

Check Your Understanding

Please answer the following ungraded questions to help you determine whether you are ready to proceed to the next lesson in the module.

(1) Does HTML require a stylesheet?

Show the Answer

No, HTML does not require CSS. If CSS is not provided to the browser, then the HTML will still render on the screen using the browser’s default styles.

(2) What is an inline style?

Show the Answer

An inline style is a CSS declaration that is applied to an HTML element directly in the HTML code. While it is a valid way to write and apply styles to HTML, inline styles are considered bad practice because they are more difficult to read and require updating the HTML file to make a style change. Using an external stylesheet creates a separation between “content” and “presentation” which makes maintenance easier because there’s less chance that the HTML is inadvertently changed when updating styles.